AIDS IN AFRICAFaces of a plague: An artist's journey into the heart of a deadly epidemicStory and Illustrations Karen Blessen

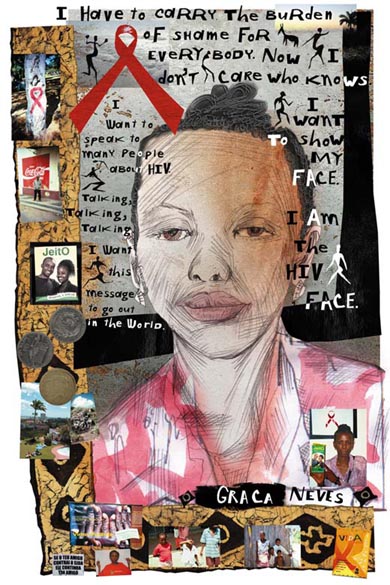

Look one way, and there's the sublime view of the Indian Ocean, with swaying palm trees, turquoise sky, luxurious hotels and happy tourists having a beer or a gin and tonic. Look in another direction, and you see layers of trash, 10 feet high, with people scouring for food or something to sell. This is Maputo, Mozambique, the city where Graca Neves lives. She's HIV-positive, and she wants to live. She's angry that she has lost two children to the disease. Doctors could have prevented the transmission of the virus to the babies she carried had they had the drug Nevirapine - but it wasn't available. She's angry because she can't get other anti-retrovirals - drugs that would keep her alive to care for her remaining child."I want to speak to many people about HIV, talking, talking, talking about it," she tells me. "I want this message to go out in the world that HIV is killing people, and I don't want other people to be in the same position that I am in. "I lost three sisters to AIDS and two of my own children. Now I am fighting against AIDS. That is my life's work. Now I don't care who knows - I want to show my face. I am the HIV face." Graca, 30, is one of several women I meet while in Africa. I have taken my journal, camera and sketchbook to Malawi and Mozambique as a member of an HIV/AIDS advisory committee for Save the Children, the international relief organization. Our group consists of two Save the Children board members, two employees and five "outsiders." My goal is threefold - to meet and talk with women who have HIV or AIDS, to understand and communicate why it is essential that we care, and to examine Save the Children's mission. More than 40 million people worldwide are living with HIV/AIDS. More than 25 million of those are in sub-Saharan Africa, according to UNAIDS, the United Nations Joint Programme on AIDS. About 44 million children will become "AIDS orphans" worldwide by the year 2010. Of those, 40 million will be in Africa. That's about five times the population of New York City. The hard facts overwhelm and distance us. But on this trip to Africa, I see faces that bring these facts home and instill me with hope. There are answers; there are things to be done. Why this disparity? How can these challenging questions be dealt with? I despair at attempting to make any sense of the chaos ... In the faces: Wistfulness, sorrow, contempt, joy, openness. The gracious beauty. The smiles. And in some, the desperation, the acceptance, the anger. - Journal entry Arriving in Africa, we enter a world where extremes co-exist - beauty and ugliness, joy and pain, color and color blindness, flesh and spirit, death and life, suffering and creativity. We see the effects of HIV/AIDS, as it devours families and de-stabilizes communities. And we also experience the unstoppable spirit of people dealing with an unthinkable enemy. We hear music bursting with joy and impulsive vitality, and we drink in the giddy love of color and pattern in the fabrics worn by women. We are surrounded by artistry - wood carvings, batiks, paintings, jewelry and baskets. And we see smiles - beautiful, warm, inviting smiles. Here, amid the complexity of Africa, AIDS is one of many problems. The per capita annual income in Malawi is the equivalent of $170; in Mozambique, it's $210, according to the World Bank. The life expectancy in each country is about 37 years - among the lowest in the world, according to UNAIDS. Mozambique is recovering from a 17-year civil war. In the villages of Malawi, people are mostly subsistence farmers, growing maize and cassava plants. If there is a crop failure, as there has been this year and last, the results are immediate. People starve. Malnutrition, malaria, tuberculosis and pneumonia are facts of life in this corner of Africa. And this, doctors told me, may be one reason why AIDS has spread so widely - its symptoms are so similar to those of the more common illnesses. At this time, intravenous drug use and shared needles don't appear to contribute significantly to the spread of the HIV virus in Malawi and Mozambique, unlike in other parts of the world, Save the Children says. Roughly 16 percent and 13 percent of the adult population in Malawi and Mozambique, respectively, have HIV, compared to 0.6 percent in the United States, according to UNAIDS. Mother Africa. I'm reminded that this is the cradle of civilization. This is the wellspring, this robust, raw presence, in your face - the heat, rats in the hotel room, monkeys grabbing food from plates, men and boys rushing toward you with their need - to sell things they've made - for money. This slap in the face that THIS, this is IT. This is IT, with the pretenses and the poseurs stripped away, with no air conditioning. This unrestrained force of nature - to BE. This is it, with no developers or concrete trucks. This is nature saying, "I AM." Loud. So clear. Needing us, tamed logicians and scientists of the world, to help, to help, to help, and hold this tiger by the tail. To keep it from devouring another loved one. - Journal entry Time magazine's Feb. 2001 report on AIDS in Africa used pseudonyms for AIDS victims and didn't use their images. A stigma surrounds AIDS in Africa. Women in Africa pay a price for speaking out - some abandoned by their families, beaten, becoming a target of gossip, losing their status in the community. In Africa, the stigma fades as knowledge and treatment information spreads and also as more and more people lose loved ones. Everywhere we go, brave people are ready to stand and talk, allowing their names and images to be used. I speak with Graca in Mozambique and, in Malawi, with two other women who are living with the disease, as well as with a teacher and a community leader - both healthy - who deal with the challenges of education and the increasing number of orphans caused by AIDS. Five women, five mothers. With hints of agony, serenity, contempt and intelligence, their eyes reveal experience and wisdom. I think their power is underestimated and underutilized. These five women have courage. They refuse to be compliant to the silence surrounding AIDS.

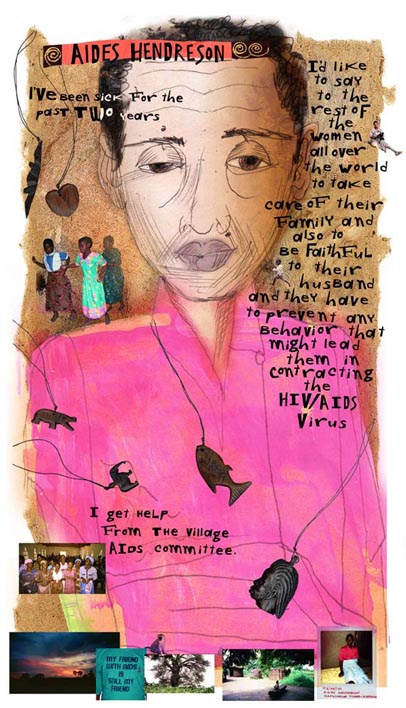

Aides HendresonThe village of Kafucheche, Malawi. The church is rocking. A few people stand away, in the corn. Goats everywhere. There are quiet spots in the village. A woman is resting on her porch with children nearby and a goat on her lap. A baobab tree towers overhead. - Journal entry We are deep in corn fields. It's uncannily familiar yet surreal. I'm from Nebraska. I know corn. On the other side of the world, I never expected to be in the middle of fields of corn. Hundreds greet us with song and dance at the village Anglican church. One of Save the Children's programs helps villages develop home-based health care for HIV/AIDS patients. We are asked to sit at the front of the church while the health-care team dramatizes their procedure. Then young girls and boys dance and play a song, warning one another about the dangers of HIV: HIV/AIDS is real. HIV/AIDS is in our community. It is not just in our community but it is amongst us gathered here. Fellow youth, it's time to watch out: AIDS is real. It has no cure. Once you have it, you are in for it. Avoid sugar daddies. Listen to parents' advice. Work hard in school. There is a better tomorrow." In this village, I meet Aides Hendreson. Her face is slack, her eyelids heavy and her gaze averted. She makes fleeting eye contact, but it appears to be an exhausting effort. Alone in her tidy house, she sits on the straw mat on the floor, legs extended, with her back to the wall. She wears a pink blouse and a light blue skirt. Like many of the villagers in Malawi, she is barefoot. She lives in a typical village house, with a thatched grass roof. Aides is 56 years old. She was married and has three children. Her husband died last year, and the three children are working in Mangochi, the larger town nearby. Her symptoms of full-blown AIDS started two years ago, with diarrhea, swollen legs, abdominal pain and bad headaches. Since she receives no anti-retroviral drugs, her prognosis is not good. Her treatment consists of home-based care through the village's AIDS committee. "I get help from them, from their medical kit," she says. "Sometimes they sweep my house and they provide me with food." The only drug in the medical kit is acetaminophen. At times, her children come to help her. HIV/AIDS has had plenty of time to spread to remote villages such as Kafucheche. Malawi's previous political regime didn't support discussion or education about AIDS, Save the Children officials say. Women such as Aides have little incentive to be tested for AIDS. The cost of the test is daunting for many Malawians. But more than that, they have nothing to gain. Life-saving treatment is not available to them. Aides says that she doesn't know exactly how she contracted the disease. "I feel sometimes that poverty could be attributed to contracting the virus," she says. "Sometimes, the thing that we do might be caused by our poverty." Graca NevesI like to spend some time in Mozambique

Graca Neves, who lives in Maputo, Mozambique, is part of Kindlimuka, an organization of people living with AIDS. "Kindlimuka" means "wake up." I talk to her at a gallery displaying a photo exhibit titled "Vidas Positivas," or "Living Positively." A photograph of Graca hangs on the wall, along with photographs of others who are HIV-positive. Some photos show people's faces, one shows a face covered by hands, and one is simply an empty black frame. The HIV infection rate is more concentrated in urban areas such as Maputo, and the rate nationwide is higher in young women than it is in young men, according to UNAIDS. Women here are generally of a lower social and economic status and have less ability to negotiate safe sex. But despite that, in each photo I take of her, Graca insistently poses with a half-gallon carton of condoms. She speaks of the harassment that she and her child face on buses, and of being kicked out of apartments. For better or worse, her involvement with Kindlimuka has given her a public profile. "It is very strange and unfair, as in this country we know that at least one person in five has HIV, although most are not aware of it," she says. "I have to carry the burden of shame for everybody." When I talk to local people about sexuality, confounding contradictions bubble up. The traditional moral structure in Malawi and Mozambique is monogamous, yet so many people are getting HIV. They're having sex with infected partners. Malawi is a self-described "conservative" society, yet there doesn't seem to be a stigma to having multiple sexual partners. For years, political leaders kept private anything to do with sex, at the peril of the people. One example that Save the Children officials give: In Mozambique, husbands work in the mines in South Africa for six months at a time. While there, they may visit prostitutes who carry the disease. The husband then brings the disease home to his wife, who transmits it to the baby she is, perhaps, carrying. Or maybe the wife is promiscuous while the husband is away, or maybe she needs money and sells herself, and she transmits the disease to someone else. Parents die, and orphans are left behind. A daughter hooks up with a "sugar daddy" (a term frequently used here), who provides money in exchange for sex. Birth control is virtually nonexistent, particularly in the villages. Until recently, introduced as part of AIDS education, condom use was held in contempt and surrounded with suspicion. Some believe that the condoms themselves transmit the disease. We were told by Save the Children staff that village headmen and elders may exercise the "privilege" of having sex with any young women they choose. Also, there are deeply held cultural traditions, such as "initiation," a coming-of-age rite, which involves a very young girl's passage into womanhood by having sex with a village man. There is a particular cruelty to AIDS, as it strikes and kills people who are in their most productive years. A generation may be lost to AIDS, while the next one is being educated and encouraged to accept change.

Chatinkha NkhomaHow Malawians greet one another:

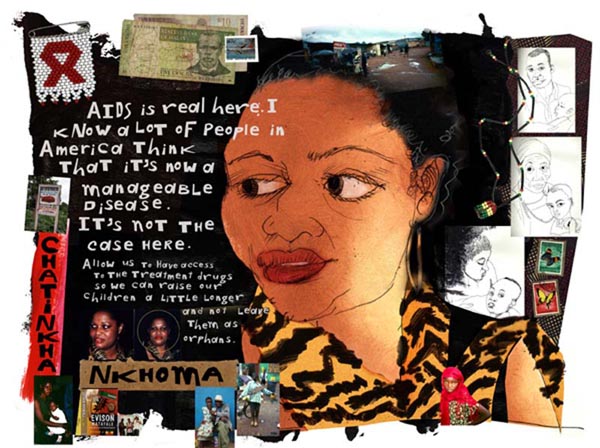

Next to a drawing of Chatinkha in my sketchbook, I write, "Isn't she beautiful?" If there's a modern face for "Mother Africa," Chatinkha, 39, is my choice. She's protective and proud of her culture, she's vibrant, she's beautiful, she speaks five languages, she got her bachelor's degree in international affairs at George Washington University in the United States, and she's HIV-positive. The partner who infected her is now dead. She lives near her family in Lilongwe, Malawi, where making coffins by hand "is the best-selling business right now," she says. She is an outspoken AIDS activist and the founder of the Global Aids Alliance-Malawi, an affiliate of Global Aids Alliance USA. She has friends on both sides of the Atlantic, and because of those friends and her own persistence, she has had access to anti-retroviral treatment for AIDS. She has testified about AIDS in Africa to a U.S. congressional subcommittee. She exudes well-being and a passion for her mission. She reminds me that while we may find some Malawian cultural rites strange - such as initiation - there are plenty of things that Malawians find surprising in our culture, such as the notion of same-sex unions. One aspect of her mission is to see that life-saving drugs get into the hands of Africans, so that mothers can live, so that fewer children will be orphaned. She's impatient with the argument that Africans would find the drug cocktails too "complicated," or that they couldn't take the drug regimens because they don't have watches. "Anyone who says that an African can't use anti-retroviral drugs is either ignorant or arrogant," she says. "Where there's a will, there's a way. Any person, if they know that their life depends on this, they will do it. The regimens that our traditional healers give are more complicated than anti-retrovirals." Malawi doesn't have a history of political activism. Under the past regime, activists critical of the government were jailed or killed. Now, in a more open atmosphere, Chatinkha lectures in workplaces and schools, to change a mind-set where "people will grumble in their homes" rather than making their voices heard. She has a common-sense approach to HIV prevention and treatment. "Let's be objective," she says. "Let's not get rid of our culture. We get rid of that, we'll be without an identity. Just integrate HIV prevention into it."

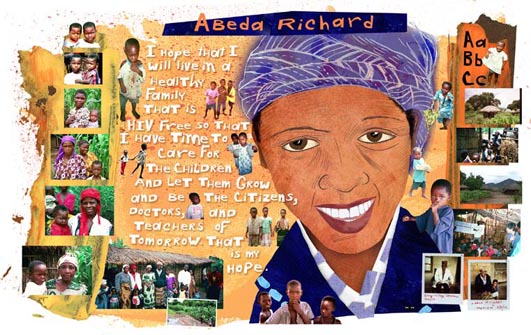

Abeda RichardI'm looking through the car window. We stop. I turn to my left and a boy is selling a large catfish, holding it right in my face. A woman carries six feet of bundled twigs balanced on her head. A man waves three live chickens at the car as we speed past at 50 mph. People hold huge colorful umbrellas to protect themselves from the elements. A child stands, watching, in the midst of tall grass. There's a bicycle with a big basket on back, and a bicycle rider with a modern backpack. - Journal entry We turn off the main road, onto a bumpy narrow path between tall fields of corn, and pull into a clearing. We're in Chapola, Malawi, at a Save the Children-sponsored Community Based Child Care center, where Abeda Richard is one of six teachers. The school is an open-air building of bamboo, twigs, branches and grass. It's bursting with one beautiful little child after another, singing, chanting their ABCs in English and in Chichewa and watching us with great curiosity. Everybody is much shorter than I am, so I hit my head on the doorway and emerge with grass and twigs all over my shoulders. This causes looks somewhere between wild hilarity and concern. In the sweltering heat, Abeda, 37, wears a heavy, dark sweater. She is married with children. Her young daughter, Mariam, leans against her while we speak. There are two constants during our conversation: Abeda's sweet, disarming smile and Mariam's direct and slightly suspicious gaze. "I hope that I will live in a healthy family that is HIV-free so that I have time to care for the children and let them grow and be the citizens, doctors and teachers of tomorrow," Abeda says. "That is my hope." Schools are of utmost importance here. Just as in the United States, parents see school as a gateway to future opportunities for their children. With more children orphaned due to AIDS, this school offers a place for socialization between orphans and nonorphans. It's also a place to monitor a child medically and to ensure that a child is given at least one meal a day. In Malawi, primary school is free. Of the qualifying students, mostly boys go on to secondary school, which is also tuition-free, but it does have related costs, such as boarding and supplies. Gender inequality prevents many girls from attending secondary school. Their lack of education and higher HIV infection rate contribute to the spread of AIDS, Save the Children officials say. About one-third of teachers in Malawi are HIV-positive. One explanation of this is that teachers, who are usually men, have a position of status in village culture and may have their pick of sexual partners. Abeda, who appears in good health, tells us that of the 250 students here today, 150 of them are orphans. The teacher becomes crucial in the life of an orphan. And every month in Malawi, 25 to 50 teachers die, according to the Malawi Ministry of Education.

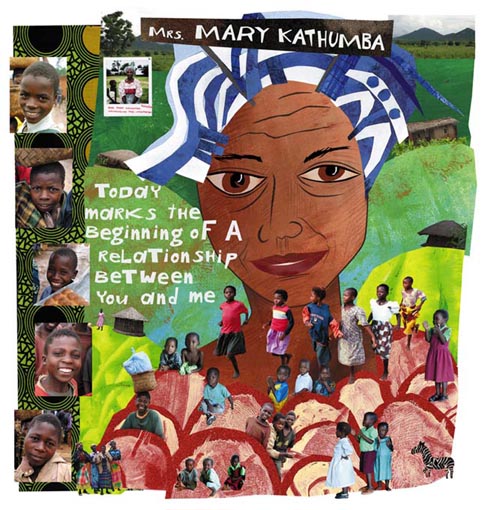

Mrs. Mary KathumbaA heady scent is in the air. Floral, lake water, earth. Scent of sweating bodies in the wet heat. The sky is a blue that I remember from childhood. Intense, unclouded by lawn mower or car exhaust. Something good, elemental, pure. - Journal entry Mrs. Mary Kathumba knows how to handle herself. She has a message, a goal. She gives me an assignment, takes my name and address, and she asks for a follow-through. Born in 1947, she's mother of eight (though one child died), and grandmother of 14. She's a leader in her village of Mpinganjira, in Malawi, and a member of the orphan care group. In the area surrounding her village, there are 30,000 orphans. The goal of the village care groups is to keep the orphans in their village and away from orphanages, so that a child will be surrounded by a familiar culture and people. As parents, teachers and those in other vital professions die, orphans face many risks - malnutrition, poor access to health care, lack of schooling, early marriages, sexual abuse and loss of inheritance and status. Families spend much-needed resources to bury loved ones. Vagrancy, crime, homelessness and HIV/AIDS increase. Communities de-stabilize, and grandparents are left with a gargantuan task. Mary's message to me: "Once you get back to Texas, I'd like you to talk about the problem that we are facing in Malawi and all the people that HIV/AIDS is real in Malawi. It has left a lot of orphans, and we are not able to support them." Mary's goal: "If Malawi received a lot of AZT or other drug cocktails to help a long life, that'd be good, for by the time that these children would become orphans, they might have completed school by then. We'd like to have a lot of the drugs, but we don't know how to ask for them." Mary's assignment to me: "It would be good if you communicated that. Whatever you communicate, whatever feedback you get, you should give us so that we should be assured that you indeed communicated that you were our advocate." This is my communication. Mangochi District HospitalOur hearts beat in the same rhythm.

At Mangochi District Hospital in Malawi, there are 240 beds and between 400 and 500 patients. We enter three wards, one where mothers hold children, one for men and one for women. Every bed is full, and very sick people are lying on the floor on mats below the beds. Except for one person's soft moaning, there is silence. No monitors beeping, no crying out for a nurse or a doctor. Each ward is arranged in successive order of illness and desperation. As we walk farther into the rooms, the patients are more emaciated, the symptoms more visible - skin lesions, glazed eyes. Each ward has one nurse, who works a 12-hour shift. The pain medication is Panadol - acetaminophen. The staff does the best it can while fighting an enormous battle with extremely limited resources. That night, in my journal, I write, "It was horrible, horrible, horrible, horrible. The hospital this afternoon. Sick mothers. Emaciated babies. "The people have been lovely to us, beautiful, gracious, so earnest in their desire to please us and make us feel welcome and honored. I admired a necklace, and it was given to me. "Our conversations of policy and public perception and ad campaigns pale in the face of the raw emotional immediacy of what we saw today. It was the belly of the beast. Ground zero. The end. What words can there possibly be?" I am overcome by emotion, and I burst into tears at the dinner table when asked, "Karen, how was the hospital?"

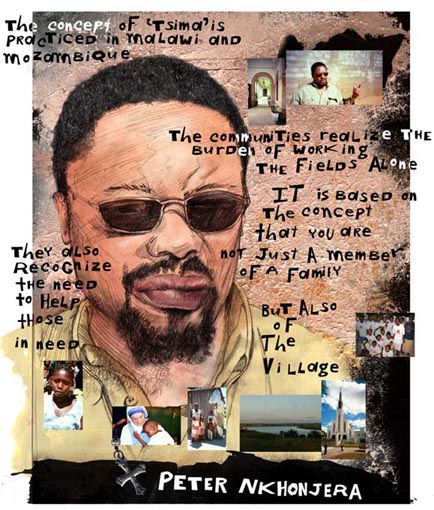

"The concept of 'tsima' is practiced in both Malawi and Mozambique. The communities realize the burden of working the fields alone, building a house, for instance. They also recognize the need to help those in need, the elderly, widows, orphans, etc. Based on the concept that you are not just a member of a family but also of the village, the community takes it upon itself to assist those that need help." - Peter Nkhonjera, assistant field director, Mozambique, Save the Children After Mangochi Hospital, my question of "Why should we care?" turns into "What can I do?" Reasons to care are clear. We care because if our hearts are awake, we mourn when met by one child who has lost both parents, let alone the unimaginable prospect of 44 million orphaned children around the world. The fundamentals of the great faiths of Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam call us to honor the simple basic human responses of compassion and generosity. When millions of spirits are diminished, can we really afford to believe that our own won't erode? We have to ask, "Who will survive?" And what kind of people will the orphans be if they grow up without the foundation of family love? How much will they hate us when they find out that we have so much? We have the drugs that could save a mother's life. We have plenty of money and stockpiles of food. Yet they starve. U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell and former President Bill Clinton call the AIDS pandemic an economic and national security crisis. Are we watching the beginning stages of breeding grounds for people who are hardened and opportunistic, who hate us enough to live to kill? Five minutes to wet our feet in the pounding Indian Ocean. No one said the word, but to me it was a baptism. We went to the water. We were bound as a group by what we had seen. We were in. - Journal entry I feel a responsibility to the people who opened up to me in Africa. Mrs. Mary Kathumba, the grandmother and village elder, left me with these words: "Today marks the beginning of a relationship between you and me." As an artist, my task is to use every communicative skill I possess, so that I can be a conduit, so that I can connect and complete the relationship. I've seen that I can't afford to feel helpless, because there are concrete things that I can do to help. Why did Save the Children invite me, an artist, to be a member of the HIV/AIDS advisory committee? I was told it was because I wouldn't bring along the cynicism of a journalist. Artists do engage and respond, often powerfully. Michelangelo, Picasso, Goya, Kathe Kollwitz and many others took on the blood and the mud, and laid the groundwork for the engaged artist. Emily Dickinson stayed in the house but unearthed words that nailed the truths of human longing and emotion. In drawing the faces of the five women, I wanted to honor them, to extend my time with them and to get to know them in the way that works most deeply for me - through the intimate act of intense eye-to-hand observation. Drawing. In going to Africa, I wondered if I would experience authentic life - that is, life not perverted by fashion magazines, advertising and every other influence that whirls around us. I had hopes of seeing the original beauty of this earth. There is hope. There are individuals dedicating their lives to good work and to helping, one child at a time. There are villages uniting to care for their own. There are well-managed organizations that do get the aid to people in need. If Coca-Cola, Surf laundry detergent and beer can be delivered throughout Africa, then there are ways to deliver life-saving drugs to sick people and to educate them on how to take these drugs. Organizations such as Save the Children are part of the answer. The group puts the HIV/AIDS conversation on the table and makes it permissible for women and men to talk about it. It helps children with immunizations, with programs that empower, support and educate the caretakers of children, with efforts to see that orphans can go to school and remain in their villages. Some governments are waking up to the long-term ramifications of HIV/AIDS. Brazil and Uganda are showing a determined political will and commitment to their populace. They are creating models of AIDS treatment and prevention, encouraging massive widespread condom use and education programs, according to Save the Children. Brazil guarantees free access to anti-retroviral therapy for people living with HIV/AIDS. Uganda has brought its estimated prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS down to around 8 percent from a peak of close to 14 percent in the early '90s, according to UNAIDS. In the developed and wealthy world, we're seeing a fascinating mix of political bedfellows. Irish rock star Bono and the Republican Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill tour Africa together, visiting AIDS clinics, schools and development sites. House Minority Leader Richard Gephardt, D-Mo., and Sen. Jesse Helms, R-N.C., agree on the urgency of foreign aid to Africa and other developing countries fighting HIV/AIDS. The U.S. Congress has recommended huge increases in our foreign aid budget, and President Bush, according to news reports, will showcase the United States' $1.3 billion commitment to fight HIV/AIDS globally at the G-8 summit in Alberta this week. In the most literal sense, Aides Hendreson, Graca Neves, Chatinkha Nkhoma, Abeda Richard and Mrs. Mary Kathumba have placed their hope in me. In telling their story, I take their trust and their hope and I give it to you. Karen Blessen (kblessen@aol .com) is a Dallas free-lance writer and illustrator. For more information on Save the Children, call 800-728-3843, or write the organization at: 54 Wilton Road, P.O. Box 980, Westport, CT 06881. RESOURCES

For more photographs and information about the HIV/AIDS advisory committee's trip to Malawi and Mozambique:

Many of the photographs used in the illustrations are copyright Mick Yates and Rob Houghton, used with permission. |

ALL STORIES:: One By One By One:: One Bullet :: In Mom's Eyes :: Luck :: A Sea of Sound :: Diary of a Confetti Engineer :: What Did He See From the Mountaintop? :: Faces of a Plague :: What turns compassion into action? :: Today Marks the Beginning If you are interested in scheduling Karen Blessen for a speaking engagement or workshop, please call 214-827-3257 or e-mail kblessen@aol.com |

Contact Karen Blessen :: kblessen@sbcglobal.net :: Karen@29Pieces.org :: kblessen@TodayMarkstheBeginning.org :: 214-827-3257 :: Email Webmaster

KarenBlessen.com. Artist and writer. Cut paper collages, illustrations,

drawings, prints, stories, journal entries, public art, and photographs are

copyright Karen Blessen unless otherwise noted.