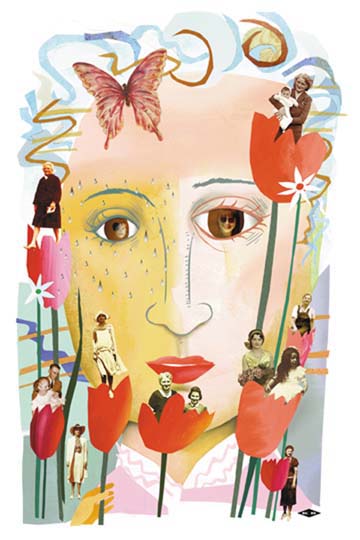

In Momís EyesStory and Art by Karen Blessen

I planted the tulips to remind me of her. It was back in 1997, the worst of times, when she had gone into the nursing home. Fifteen hundred tulip and daffodil bulbs would be something to look forward to, I thought: something to remind me of when my mother was straight, young, tall and proud. Some people go to Colorado or the Hamptons in the summer. I migrate from Dallas to Nebraska in the spring. As usual, it has been windy this season; the neighbors' screen doors were whipping open and shut, and my tulips were getting shredded. So I cut them every morning and gave away the bouquets as fast as I could. She hated the wind Ö it was hard on hairdos, and hair was a big thing for her. I have to smile at the memory of her, lipstick perfect, hands on her hips, frustrated, stomping her foot, throwing her head back and pushing her hair out of her eyes, saying, "This damned wind! Look what it's doing to the tulips!" My mother, Alice Blessen, died two years ago, on Mother's Day, in the small town of Columbus, Neb., where she'd lived her entire 90 years. I was a Mama's girl, an only child. I loved her company, loved drawing her face, loved the touch of her fingertips. She was one of my favorite people to talk to and about. She cracked me up, occupied many pages in my diaries, maddened me, and got under my skin faster than anyone else. She was lost in increments -- chunks of her life falling away. The first blow was Dad's lung cancer and death. Then her own arthritis and heart problems worsened; she couldn't drive any longer, couldn't go shopping or sit through a movie. Then she couldn't walk up the stairs. No prior loss compared to the first heartbreak of driving my mother to a nursing home, and then her eventual death. Even though she was 90 and I was 46, nothing ever had taken me lower, or left me more confused and fearful about my own life and future.

My grandparents were farmers outside of Columbus, and Mom was the second of five children. She worked on the farm until she was 44 years old. That's when she married my dad, moved into town, and had me. In pictures of her before marriage, she's either in overalls (her farm work clothes) or in Katharine Hepburn-style tailored suits (her town, church, and holiday clothes). Other than church or holidays, my memories are of her dressed mostly in cotton housedresses and aprons. Later, after she couldn't wear high heels, she converted to slacks and never had a dress on again. She became prematurely gray in her 30s, and she didn't dye her hair. Proud of her "white cloud," as I called it, she dressed to accentuate it and, in her later years, loved being told she looked like Barbara Bush. She was an excellent cook, with a flair that seemed intuitive and effortless. Throughout our lives, in the simplest of kitchens, food was satisfaction, sharing, a way to please and a road to peace. She was gracious and warm, often extending her hand to hold the hand of whoever she was talking to. It was an act of reaching out, and also a subtle exposure of her own need and contradictions. She was both farm and town, strength and hesitancy, joyful and thin-skinned. She was outspoken and timid, religious yet eluded by faith in her everyday worries. She was loving and fearful, capable yet needy. She could be a drama queen -- always a paper-thin distance from rivers of tears. One day while I was watching television in the living room, she came down the steps, threw herself on the couch, blurted out, "We have dandelions!", draped her handkerchief over her face and collapsed into tears. Even then I knew that this was about more than dandelions, but what can a daughter say? If I fell down the steps, she began crying before I did. It was empathy, but it also made me want to protect her when I was the one who'd been hurt. So early on, I fell into a pattern of seldom sharing my own troubles with her. My friends who knew her describe her with words like "serene ... she listened ... approachable ... soft ... the kitchen" (this last from someone who fondly remembers her cinnamon rolls and chocolate-chip cookies). And my favorite, "pink." Though hardly diminutive, she was pink. She was pink cheeks, softness, a grown woman possessing proud feminine vitality and a baby-like innocence and need. I adored her.

As Mom and Dad aged, I felt the responsibility of their care looming before me. Many of my adult decisions were made with this in mind. To build a career that would allow me to go back and forth between Texas and Nebraska and still keep my work, I started my own illustration business, and began to develop clients nationally. My husband and I bought a place I'd always loved, the old neighborhood storefront in Lincoln, where he'd lived when we met in the 1970s. As much as I cared for my parents, I understood my need for a retreat. I was needed in Nebraska more and more after Dad was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1993. Mom and I seemed like Demeter and Persephone, the mother and daughter in Greek mythology, with the daughter splitting her life and time between her mother and her husband. Though I was aware of the cost and the hardships that my absence placed on my husband, I was willing to pay the price This was what I needed and wanted to do. Watching a parent's life come to a close is a murky brew of nightmarish health crises, humiliations, huge bills, practical details and one's own feelings of loss. This was what I had feared most and, for the most part, it lived up to its billing. Still, dark as the mix was at times, there also were many moments of grace. Mom was used to doing heavy work, then washing the muck off and dressing up, going out and having fun. She had always been the one taking care of others. Now she needed help, and she didn't take well to coming face-to-face with her own frailty. She was ticked off, she felt sorry for herself, and I understood. Neither she nor Dad went gently into that good night. Dad's death and her heart attack meant that she couldn't live in her own home without help. She had never paid bills, written checks, or done banking or bookkeeping, so I took care of all that. She was afraid to drive any more (and society was the safer for it). People had to be hired to help her with bathing, her hair, meals, laundry, cleaning, doctors' appointments and shopping. Her days at home were very quiet and very long. By 1997, the crises were frequent. She would fall. She would have episodes when she couldn't breathe. Once she complained to the doctor about feeling nervous and was given anti-depressants. She had an extreme reaction to the medication and was found in the front yard, hallucinating that Dad and a bunch of other men were out there needing breakfast. She told them she didn't do that anymore. A place opened up at the local nursing home much faster than we had expected, only three days after she went on the waiting list. I sat down next to her and told her, and she said, "I think we'd better do this." I told the nursing home that we'd take the room. We needed to move her there the next day. I held it together until I went upstairs and looked around at our bedrooms, her dressing table, her jewelry, and I realized that this was the last day of life as I knew it. For the first time since I was a child, I couldn't control my tears in front of my mom. But she surprised me. She had no tears. She took my hand, asked me to lie down next to her, put her arms around me and said, "Karen, we know that this is the way it has to be." At first, there were parts of life in a nursing home that she actually enjoyed. After being alone so long, she had friends around her again; she could talk and gossip. For the most part, the people who worked there were compassionate in the midst of difficult circumstances. The food, however, was horrid, and no amount of complaining made a difference. She lost weight rapidly and began a pattern of catching every virus that went through the facility. My life at this time was crazily jumbled and exhausting. Behind one door was Mom, frailty, illness, worry and grief. Open another door, and a room tumbled out, full of all her possessions to go through, an auction to plan, a house to sell, bills to pay. Behind another door was my artwork, which brought me joy, satisfaction and deadlines. I almost forgot that there was another room back in Texas, waiting for me. Friends, my husband, family, my work and my faith got me through this. But then my cat, Luella, who went everywhere with me, stopped eating and walking. She was diagnosed with feline leukemia and had to be put down. That took me over the edge. I wrote in my diary: "Everything comes to loss." That's when I planted the tulips and the daffodils.

She lived long enough for me to bring her the year's first bouquets of tulips and daffodils. She was ready to let go of this life, and she needed me to tell her that I would be OK here without her. I began to understand that it wasn't right to try to hold her here any longer. My job was to help her die as comfortably and peaceably as possible. However, "peaceably" wasn't exactly the way she planned to leave us. As my cousin Sonny said, after one visit with her in the hospital, "That Alice is a bearcat." "Terrorist" is another word that comes to mind -- at least, she sure knew how to strike terror in me during those last days. She would find wild strength and pull her IVs out She would keep her roommates up all night with demands for the nurses to rearrange her pillows. She would be found sitting on top of overturned trash cans, even though she hadn't walked on her own in months. Dying can be a hard thing to accomplish. It's not like in the movies, where someone turns their head to the side, closes their eyes, and that's it. Three days before the end was a particularly hard day. That evening, as I prepared to go home, she turned to me and said in a clear voice: ``I don't have much time left. The dear Lord is going to take me soon. I've had a good life. I've loved you since the first time I saw you, and I always will. Be a good girl, OK? And drive home safely.'' I still can't repeat those words without falling apart. I prayed that I would be with her when she went, and I was. She could no longer speak, but she was holding my hand, and I kept urging her, "Relax now, Mom. Everything's going to be OK." The room was full, though she and I were the only people in it -- full of love, full of spirit. When she went, I felt a flood of calm, and I thought: "So this is 'The peace that passeth all understanding.'" I knew that she was now in a safe place. She died at 12:30 p.m. on Sunday, May 10, 1998 -- Mother's Day. Perfect. After the funeral, I closed out the checking account that she and Dad had opened when they were first married. The bank clerk brought out the form they'd filled out in 1951. The sight of both of their signatures from so long ago, from the very beginning of our lives together, brought the loss of them home to me. Right there in the bank, I became like her -- a river of tears. She was pink, she was soft, feminine, girly things Ö lipstick and powder, high heels and aprons. She was the sun; I was the planet orbiting around her. And she was gone. "If everything comes to loss, you might as well have a lot to lose." That was written in my diary after Mom died. At some moments, peace shifted to fatigue. Then a joyless, depleted state would overtake me for weeks at a time. There were moments of feeling I was made of broken chopsticks, held together by masking tape. I was unable to imagine a future. Sometimes I felt that my life, too, was at an end -- half-wishing that I could be with them. It wasn't as simple as grieving the loss of my mother. It had to do with witnessing what life comes to -- of all the possessions out on the lawn, all the cracked furniture and sticky dolls, like an open wound for the whole world to see. If I was a daughter no longer, who was I? If I had spun off my orbit, what was my place in the world? If I'm not a planet, or a sun, am I just another speck in the firmament? Slowly, I came to terms with the loss of Mom, and I began to arrive into my own life. I came to understand that we are shaped by our parents, by God, and by the circumstances of our surroundings. I was my parents' child, but I am also a child of God and of the greater world.

After a devastating loss, life still is there, beckoning us to come on now, come on. If we step forward fearlessly, we will be rewarded with times of great joy and celebration -- and with absolutely no guarantee that there won't be more sorrow to trudge through. If we withdraw out of fear or timidity, we will be left to wither silently, on our own. The tulips are like that -- like life itself. Each spring they burst fearlessly out of the ground, straight and tall, extending their cups to the sky, taking whatever wind or storms come their way, then opening their petals to the warmth and light when the sun comes out. Now, when I extend my hand, as she did so many times, and give the tulips away, it's about cups of warmth, light, color and joy -- the affirmation of participation in this thing called life. I'll always love you, Mom. (DMN addition) Dallas artist Karen Blessen was on the Dallas Morning News team that won a Pulitzer Prize in 1989, the first graphic artist to be so honored. Her art has graced books, newspapers, magazines, posters and billboards around the world. |

ALL STORIES:: One By One By One:: One Bullet :: In Mom's Eyes :: Luck :: A Sea of Sound :: Diary of a Confetti Engineer :: What Did He See From the Mountaintop? :: Faces of a Plague :: What turns compassion into action? :: Today Marks the Beginning If you are interested in scheduling Karen Blessen for a speaking engagement or workshop, please call 214-827-3257 or e-mail kblessen@aol.com |

Contact Karen Blessen :: kblessen@sbcglobal.net :: Karen@29Pieces.org :: kblessen@TodayMarkstheBeginning.org :: 214-827-3257 :: Email Webmaster

KarenBlessen.com. Artist and writer. Cut paper collages, illustrations,

drawings, prints, stories, journal entries, public art, and photographs are

copyright Karen Blessen unless otherwise noted.

In her heyday, Mom was tall and striking. She was an inch short of six feet and had more nerve than I've ever had when it came to wearing high heels. She wore them into her 70s, which was way longer than common sense or her spine dictated. But she loved the way they looked. Among her most prized possessions were two expensive pairs of high-heeled spectators that she bought in Omaha years ago. She made sure I got them.

In her heyday, Mom was tall and striking. She was an inch short of six feet and had more nerve than I've ever had when it came to wearing high heels. She wore them into her 70s, which was way longer than common sense or her spine dictated. But she loved the way they looked. Among her most prized possessions were two expensive pairs of high-heeled spectators that she bought in Omaha years ago. She made sure I got them. We grow in our mother's body -- one organism. For a human being, it is the most mysterious and profound creative act possible, for the child literally is part of the mother. If a mother and child can look into one another's eyes and see love and acceptance, it is a life-affirming reinforcement of our existence and who we are. If that look is absent, it is a whole different foundation on which to build a life. When I looked into Mom's eyes, saw the love there and basked in her radiant smile, I knew I had a place in the universe, and she was the sun at the center of my orbit. It wasn't always a tight orbit -- I'd detached enough to have my own dreams, goals, and loves. But it was an orbit nevertheless. I went 75 miles away to the University of Nebraska in Lincoln (Dad said she sobbed all the way home). I traveled to Europe for three months by myself (she sobbed for days in the kitchen before I left). I moved to New York City (more wailing), and then to Dallas (a huge relief for her after New York). She was enamored of the Dallas TV show in the 1980s and was down to visit Southfork within a month of my moving here. I left home, but I always circled around back to her.

We grow in our mother's body -- one organism. For a human being, it is the most mysterious and profound creative act possible, for the child literally is part of the mother. If a mother and child can look into one another's eyes and see love and acceptance, it is a life-affirming reinforcement of our existence and who we are. If that look is absent, it is a whole different foundation on which to build a life. When I looked into Mom's eyes, saw the love there and basked in her radiant smile, I knew I had a place in the universe, and she was the sun at the center of my orbit. It wasn't always a tight orbit -- I'd detached enough to have my own dreams, goals, and loves. But it was an orbit nevertheless. I went 75 miles away to the University of Nebraska in Lincoln (Dad said she sobbed all the way home). I traveled to Europe for three months by myself (she sobbed for days in the kitchen before I left). I moved to New York City (more wailing), and then to Dallas (a huge relief for her after New York). She was enamored of the Dallas TV show in the 1980s and was down to visit Southfork within a month of my moving here. I left home, but I always circled around back to her. In early 1998, a lingering cold left Mom short of breath and uninterested in food. The cold became pneumonia, and things fell apart swiftly. There were maddening episodes of bad judgment and cavalier care on the part of some of her doctors and health-care workers, but I'm not sure that the course of events could have been changed.

In early 1998, a lingering cold left Mom short of breath and uninterested in food. The cold became pneumonia, and things fell apart swiftly. There were maddening episodes of bad judgment and cavalier care on the part of some of her doctors and health-care workers, but I'm not sure that the course of events could have been changed. Every day, I miss her radiant smile, her soft touch, and my reflection in her eyes. I have bountiful memories of her. There are great gifts in life: love, faith, work that engages us. One of the greatest gifts given to a mother is the ability to reassure her children of their place in the world. And my greatest gift was to have a mother who, with her eyes, used this power to bestow such confidence. I was blessed to have her, my guiding light. We were two complicated women with the simplest and most uncomplicated connection.

Every day, I miss her radiant smile, her soft touch, and my reflection in her eyes. I have bountiful memories of her. There are great gifts in life: love, faith, work that engages us. One of the greatest gifts given to a mother is the ability to reassure her children of their place in the world. And my greatest gift was to have a mother who, with her eyes, used this power to bestow such confidence. I was blessed to have her, my guiding light. We were two complicated women with the simplest and most uncomplicated connection.