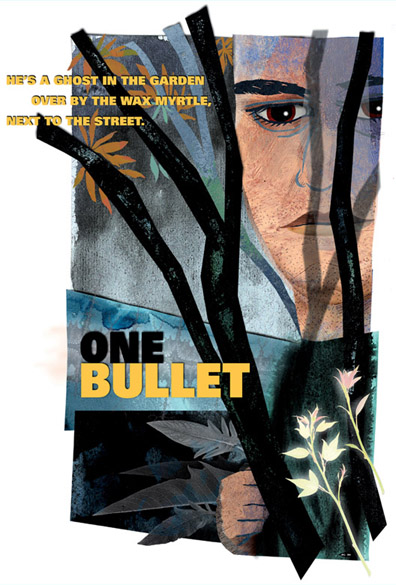

One BulletStory and illustrations by Karen Blessen

* * * * * *

Look at the world you know, this apparent peaceful existence that extends - what - 5 inches from you? 5 blocks? It isn't so everywhere. What happens when two worlds collide?

- Journal entry, April 28, 2003

* * * * * *

On the Saturday night of the shooting, we turned on the 10 o'clock news on TV to see how they covered the murder. Only one station mentioned David's death.

His murder made barely a ripple in the local media's consciousness or in the lives of most Dallas citizens. It was just one bullet, and one murder in a year when there were 229 murders in our city, 1,238 murders in Texas, and 15,517 in the United States, according to law enforcement sources.

The bullet that killed David was a jacketed .357-inch diameter bullet that could have come from a .38 Special or a .357 Magnum. It had the impressions of five "lands and grooves" - twisting incisions on the inside of a gun barrel that give a bullet its stability and accuracy - with a right-hand twist. It was medium-caliber, but not a "cop killer" bullet.

Bullets are cheap. Pistol bullets come in boxes of 50 and cost from $5 to $20 a box. The bullet that killed David cost the shooter less than 50 cents.

One bullet. And look at what it did.

* * * * * *

The shock of it turns to anger, to denial, to feeling like a coiled snake ready to pounce. The heart cannot turn to leather.

- Journal entry, Aug. 26, 2000

* * * * * *

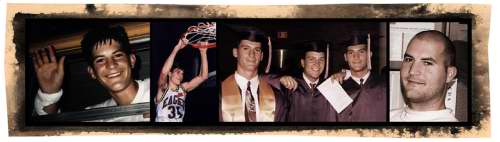

At David's funeral, a crowd of more than 1,500 mourned his death. He was a 1992 graduate of Richardson High School and a 1997 graduate of Texas Tech University.

For three years, he worked in Financial Services at H.D. Vest. He was involved in a serious, committed relationship with a young woman who teaches elementary school in Richardson.

His mother, Linda Beth, died last year of cancer. His father declined interviews for this story and did not want to be named. David is survived by five brothers - Matthew; Jonathan, who is David's fraternal twin; Jacob; Peter and Joshua.

The two young men with David on the night of the murder were Mark Hoesterey and Clay Odom, at the time both architects at a local firm.

Court records, court testimony and police reports tell the following story: Within 18 days of the murder, three teenagers were arrested. Two of them were caught on video buying snack food and gas with Mark Hoesterey's credit card at an Exxon station at Danieldale and Highway 67 in Duncanville - 29 minutes after the killing.

A fourth teenager, Keith Wilson, 18, was with the three that night. He was not arrested because there was no evidence that he got out of the car during the robbery and murder or that he used the credit cards.

The other three, Diomedes Titus "D.T." McNeal, 18; Brandon Woodard, 19; and Cornelius Richardson, 18, were jailed and indicted. The gun was never found, and the victims were not able to positively identify the perpetrators.

Arrests were made on the basis of the videotape, credit-card use and statements to police made by Mr. Wilson, Mr. Woodard and Mr. Richardson. All three say that D.T. McNeal was driving on the night of the robbery and murder. Statements by Mr. Woodard and Mr. Richardson put the gun in Mr. McNeal's hand when the shot was fired. Mr. Wilson, in his statement, said he saw Mr. McNeal and David McNulty "wrestling" just before the gunshot.

Mr. McNeal pleaded guilty to aggravated assault and murder. He accepted a plea bargain with a 12-year prison term, and he is now serving in the Telford Unit in New Boston, Texas. He will be eligible for parole after serving one-half of his sentence. To this day, he denies that he was the shooter.

In May 2002, Brandon Woodard was offered but did not accept an eight-year plea bargain. A jury found him guilty of being "party to" a capital murder. He is now serving a life sentence, with possibility of parole in 40 years. He has appealed his conviction. Cornelius Richardson, who did not get out of the car at the scene of the crime but did use the credit cards, served two years in county jail and was released.

And me? The murder came to my house. I couldn't deny its impact. I wrote down my thoughts and observations. I began a series of interviews with those in the immediate path of destruction.

* * * * * *

Silence is something to shatter, so that I won't be able to hear a gunshot, a scream, frantic pounding at the door, or a siren. I haven't wanted to be in the quiet, the solitude, to listen, to do what I do. Mark's experience is evidence that there are some things in life that you simply CANNOT prepare for.

- Journal entry, Nov. 14, 2000

* * * * * *

MARK HOESTEREY Mark Hoesterey, now 29, was the one who pounded on my door, screaming, "Open the door! Let me in!" He and David had been close friends since high school.

They'd been fraternity brothers and roommates at Texas Tech. They shared a passion for sports and fun, but they also came to each other for consolation - whether it was about Mark's anxieties or David's concern about his mom's cancer.

On the night of Aug. 18, 2000, Mark, David, and Clay Odom, Mark's friend from work, had a few beers and went to dinner at the now-defunct Lone Star Oyster Bar on Greenville Avenue. After dinner, they decided to hear a Texas country band named Speed Trucker at Lakewood Bar and Grill. At closing time, they got in Mark's Isuzu Rodeo. Mark was driving, David was in the passenger seat, and Clay was in the back seat.

"Even coming home, we had smiles on our faces," Mark recalls.

They were driving north on Abrams. They were at a stoplight when Mark's Rodeo stalled and may have rolled back and tapped a small white car behind them. The white car followed Mark, who turned west onto Vickery Boulevard and slowed down. Then a third car passed Mark and pulled in front of him, cutting him off so that he couldn't go forward.

"We had our windows rolled down," Mark says. "A guy jumped up. He held the gun to my head. I took my hands off the wheel. He grabbed the keys and said, 'You're [expletive] now.' He opened up the door and said, 'Give me your money.' Then another guy jumped in the back with Clay. Clay said, 'Let us go, let us go, take the car, take anything you want.' The guy with a gun said, 'No, we're going for a ride. We're going for a ride tonight.'"

David had gotten out of the passenger seat - possibly to talk to the people in the white car. David walked around to the back of the driver's side of Mark's Rodeo and may have surprised the gunman. We don't know. "David might not have known that he even had a gun," Mark says.

There was a shot. The shooter and his friends fled. There has not been any evidence that the people in the white car were involved in the crime. They turned around and sped toward Abrams and have never been identified.

Mark recalls the moments after the shot. "I thought somebody had just punched David," he says. "When I ran up to him, his eyes were open. He looked fine. I didn't think he'd been shot. I dragged David out of the street and to the lawn.

"When I had him on the sidewalk, I started CPR. I was giving him mouth-to-mouth. I ran up to two houses - one was real dark and then I ran up to your house."

Mark's friend Clay had run toward Abrams. He jumped a tall fence into the back yard of our neighbor, who was just coming home from a club. The two of them ran back to David. Our neighbor helped with CPR while Clay prayed.

"I remember David's eyes being wide open the entire time," Mark says. "I had blood on my hands and all over my face. He was spitting blood all over me. That view is the most vivid - looking down into his eyes and giving him CPR and then not having anything happen. He was completely still.

"Immediately afterward - I couldn't talk, I was numb," he says. "I didn't sleep for about four days. I really couldn't deal with it. I just lay on the couch. I couldn't concentrate on anything. I was hurting so bad and feeling so much responsibility. I kept thinking about it, over and over again, trying to figure out what happened or what I could have done differently."

After David's death, Mark displayed the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He got counseling for trauma.

"Very bad things do happen to good people," he says. "People shouldn't be fooled that it couldn't happen to them. It can. The trauma that I suffered is a little bit different" than for others who loved David - particularly because of the lasting images from that night. "The details will be embedded in my mind forever.

"It's like a bad movie that just plays over and over. The first year, that movie was playing all day long. Since then, I've thought a little bit less about it, but there's not a day that goes by that I don't think about what happened that night. The sheer horror of it all - the blood, the blood on me. It's as clear as a photograph.

"I'd like people to know how callous these people were - and how desensitized they were to what they did - a carjacking, a robbery and a murder, then, 29 minutes later, using my credit card to fill up their car and buy snacks.

"I don't think anyone can really understand. It's not correctable. There's not a fix. It's not like you can just say, 'Well, do this and it'll all be better.' It was very much an isolating experience. I overheard someone saying, 'Why can't he just get over it?' People can see that I'm not all better, that I still have some issues. No one would understand that, unless they were kneeling over their best friend trying to blow a little life back into that person.

"I don't know if I'll ever be able to accept it. In order to accept it, you'd want to say that there was a bigger meaning behind it - 'Everything happens for a reason.' Well, what [reason]?" Mark Hoesterey, now 29, was the one who pounded on my door, screaming, "Open the door! Let me in!" He and David had been close friends since high school.

They'd been fraternity brothers and roommates at Texas Tech. They shared a passion for sports and fun, but they also came to each other for consolation - whether it was about Mark's anxieties or David's concern about his mom's cancer.

On the night of Aug. 18, 2000, Mark, David, and Clay Odom, Mark's friend from work, had a few beers and went to dinner at the now-defunct Lone Star Oyster Bar on Greenville Avenue. After dinner, they decided to hear a Texas country band named Speed Trucker at Lakewood Bar and Grill. At closing time, they got in Mark's Isuzu Rodeo. Mark was driving, David was in the passenger seat, and Clay was in the back seat.

"Even coming home, we had smiles on our faces," Mark recalls.

They were driving north on Abrams. They were at a stoplight when Mark's Rodeo stalled and may have rolled back and tapped a small white car behind them. The white car followed Mark, who turned west onto Vickery Boulevard and slowed down. Then a third car passed Mark and pulled in front of him, cutting him off so that he couldn't go forward.

"We had our windows rolled down," Mark says. "A guy jumped up. He held the gun to my head. I took my hands off the wheel. He grabbed the keys and said, 'You're [expletive] now.' He opened up the door and said, 'Give me your money.' Then another guy jumped in the back with Clay. Clay said, 'Let us go, let us go, take the car, take anything you want.' The guy with a gun said, 'No, we're going for a ride. We're going for a ride tonight.'"

David had gotten out of the passenger seat - possibly to talk to the people in the white car. David walked around to the back of the driver's side of Mark's Rodeo and may have surprised the gunman. We don't know. "David might not have known that he even had a gun," Mark says.

There was a shot. The shooter and his friends fled. There has not been any evidence that the people in the white car were involved in the crime. They turned around and sped toward Abrams and have never been identified.

Mark recalls the moments after the shot. "I thought somebody had just punched David," he says. "When I ran up to him, his eyes were open. He looked fine. I didn't think he'd been shot. I dragged David out of the street and to the lawn.

"When I had him on the sidewalk, I started CPR. I was giving him mouth-to-mouth. I ran up to two houses - one was real dark and then I ran up to your house."

Mark's friend Clay had run toward Abrams. He jumped a tall fence into the back yard of our neighbor, who was just coming home from a club. The two of them ran back to David. Our neighbor helped with CPR while Clay prayed.

"I remember David's eyes being wide open the entire time," Mark says. "I had blood on my hands and all over my face. He was spitting blood all over me. That view is the most vivid - looking down into his eyes and giving him CPR and then not having anything happen. He was completely still.

"Immediately afterward - I couldn't talk, I was numb," he says. "I didn't sleep for about four days. I really couldn't deal with it. I just lay on the couch. I couldn't concentrate on anything. I was hurting so bad and feeling so much responsibility. I kept thinking about it, over and over again, trying to figure out what happened or what I could have done differently."

After David's death, Mark displayed the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He got counseling for trauma.

"Very bad things do happen to good people," he says. "People shouldn't be fooled that it couldn't happen to them. It can. The trauma that I suffered is a little bit different" than for others who loved David - particularly because of the lasting images from that night. "The details will be embedded in my mind forever.

"It's like a bad movie that just plays over and over. The first year, that movie was playing all day long. Since then, I've thought a little bit less about it, but there's not a day that goes by that I don't think about what happened that night. The sheer horror of it all - the blood, the blood on me. It's as clear as a photograph.

"I'd like people to know how callous these people were - and how desensitized they were to what they did - a carjacking, a robbery and a murder, then, 29 minutes later, using my credit card to fill up their car and buy snacks.

"I don't think anyone can really understand. It's not correctable. There's not a fix. It's not like you can just say, 'Well, do this and it'll all be better.' It was very much an isolating experience. I overheard someone saying, 'Why can't he just get over it?' People can see that I'm not all better, that I still have some issues. No one would understand that, unless they were kneeling over their best friend trying to blow a little life back into that person.

"I don't know if I'll ever be able to accept it. In order to accept it, you'd want to say that there was a bigger meaning behind it - 'Everything happens for a reason.' Well, what [reason]?"

* * * * * *

I questioned, "Where was God in this? Where was God that night? Did David have angels? If he did, for God's sake, where were they? Standing by, tongue-tied? Mute observers?"

- Journal entry, Dec. 23, 2000

* * * * * *

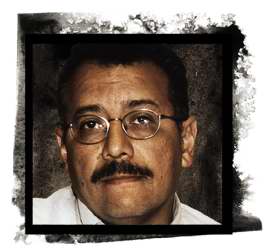

DANNY MUNIZ Danny Muniz, the homicide detective who came to my door after the murder, tries to answer my question about angels.

"It's ironic that a homicide detective should believe in guardian angels, but I think there's such a thing," he says. "Really, guardian angels aren't interested in temporal, theological or spiritual terms. The guardian angel doesn't care if you break your leg or if you die. What your guardian angel cares about is your soul. He wants you to go to heaven."

Detective Muniz had worked in homicide for 21/2 years at the time of David McNulty's death. He's married and has five children - three daughters and two sons. When I ask Mr. Muniz, who is Catholic, what gives him strength to do this work, he says, "My faith and what it teaches me about life."

Notifying David's parents about his death was "particularly difficult," Mr. Muniz says, because it was a total surprise to the family. In some cases (for example, the murder of a drug dealer), Mr. Muniz tells a mother that her son's been killed, and the mother will reply, "Who shot him?"

"It's as though she not only anticipated his death, but has a list of possible suspects in her head already," he says.

"The McNulty case was atypical in how quickly it came together," he says. "This case had multiple suspects, a heinous nature to the crime. Things got out, and it got solved."

About 65 percent of all murders in the United States in 2000 involved guns, according to the FBI. Of the dozen murders that Mr. Muniz investigated in 2000, 11 involved guns.

I ask Mr. Muniz if he thinks there should be fewer guns on the street.

"No, I think there should be fewer fools on the street," he says. "Humanity needs to learn to love humanity again - that the value of a person's life is more valuable than anything else.

"That's just the kind of society we live in - where it's OK to take a life," he says. "So when we live in that kind of society, the instrument we use to take that life could be anything. There are too many heartless people.

"It's been my sad experience to find that people are not sorry they've murdered," he says. "I thought that people would be contrite, they'd wish they could take it back. That they'd say, 'Oh, I wish I hadn't done that. I wish there was some way to erase what happened.'

"But no. They do not care. It's over, it's done, and, 'I'm sorry you caught me,' not, 'I'm sorry that they're gone.' It's a chilling experience, really, to meet somebody, to talk to somebody, who is totally indifferent to another life being snuffed out, especially when they're the ones who did it."

Homicide detectives, he says, "have a very dark sense of humor. We say the most awful things. It's part of coping, it's part of dealing with it. I see dead people all the time. It's not a problem. A couple of years ago, I saw a child, and that's a problem. So it depends. Think about it. Why is 'callused' a negative word? The body produces calluses for a reason. So I have calluses."

"If I don't get [a case] solved, justice will still come around. My job is not to bring justice. My job is to investigate, find the truth and take the truth to somebody beyond me - to the attorney of the state. The state has to present the case to the jury, and then the jury will deliver justice. That's their job - to deliver justice. If I don't leave anything undone in that search for the truth, then I'm at peace."

I ask Mr. Muniz if he believes in the existence of evil. He says, "Evil, as I understand it, is not an entity. It is the absence of good. I don't see evil as a power that swoops and invades somebody."

Two of Mr. McNeal 's friends told police that he was the shooter, and Mr. Muniz believes them.

"There's nothing different about D.T., except who he decided to listen to," he says. "D.T. listened to the bad influences in his life and in his own mind. So he didn't care about anybody else. It was just a horrible, tragic accident that he collided with David on that day. But it could have been absolutely anybody else. So I don't think we can avoid that kind of evil."Satan doesn't reach up and kill somebody. It's a human being that kills a human being."

At D.T. McNeal's court hearing, Peter McNulty, one of David's brothers, said, "I forgive you."

Mr. Muniz was moved by this. He says, "That was what I would want my children to say. Because Christ was explicit about this. When a person forgives another person, it is the most divine thing we do. When Peter did that, he and his parents rocketed to the top of my esteem list. Because - there's peace."

In November of 2002, Mr. Muniz transferred to the sexual assault unit, so that he could spend evenings with his children. He tells me about helping his daughter with her homework.

"I blithely quote Scripture that we're created in the likeness and image of God," he says. "What I don't often think about is, 'What part of us is like Him?' Does He have arms and legs? No. It's an energy, it's intellect, it's reason. My little girl was studying for a science test and she threw out the Law of Conservation of Energy, which states, 'Energy cannot be created or destroyed.' I told her, 'Well, that's God. You can't create Him. You can't destroy Him. God is energy.'" Danny Muniz, the homicide detective who came to my door after the murder, tries to answer my question about angels.

"It's ironic that a homicide detective should believe in guardian angels, but I think there's such a thing," he says. "Really, guardian angels aren't interested in temporal, theological or spiritual terms. The guardian angel doesn't care if you break your leg or if you die. What your guardian angel cares about is your soul. He wants you to go to heaven."

Detective Muniz had worked in homicide for 21/2 years at the time of David McNulty's death. He's married and has five children - three daughters and two sons. When I ask Mr. Muniz, who is Catholic, what gives him strength to do this work, he says, "My faith and what it teaches me about life."

Notifying David's parents about his death was "particularly difficult," Mr. Muniz says, because it was a total surprise to the family. In some cases (for example, the murder of a drug dealer), Mr. Muniz tells a mother that her son's been killed, and the mother will reply, "Who shot him?"

"It's as though she not only anticipated his death, but has a list of possible suspects in her head already," he says.

"The McNulty case was atypical in how quickly it came together," he says. "This case had multiple suspects, a heinous nature to the crime. Things got out, and it got solved."

About 65 percent of all murders in the United States in 2000 involved guns, according to the FBI. Of the dozen murders that Mr. Muniz investigated in 2000, 11 involved guns.

I ask Mr. Muniz if he thinks there should be fewer guns on the street.

"No, I think there should be fewer fools on the street," he says. "Humanity needs to learn to love humanity again - that the value of a person's life is more valuable than anything else.

"That's just the kind of society we live in - where it's OK to take a life," he says. "So when we live in that kind of society, the instrument we use to take that life could be anything. There are too many heartless people.

"It's been my sad experience to find that people are not sorry they've murdered," he says. "I thought that people would be contrite, they'd wish they could take it back. That they'd say, 'Oh, I wish I hadn't done that. I wish there was some way to erase what happened.'

"But no. They do not care. It's over, it's done, and, 'I'm sorry you caught me,' not, 'I'm sorry that they're gone.' It's a chilling experience, really, to meet somebody, to talk to somebody, who is totally indifferent to another life being snuffed out, especially when they're the ones who did it."

Homicide detectives, he says, "have a very dark sense of humor. We say the most awful things. It's part of coping, it's part of dealing with it. I see dead people all the time. It's not a problem. A couple of years ago, I saw a child, and that's a problem. So it depends. Think about it. Why is 'callused' a negative word? The body produces calluses for a reason. So I have calluses."

"If I don't get [a case] solved, justice will still come around. My job is not to bring justice. My job is to investigate, find the truth and take the truth to somebody beyond me - to the attorney of the state. The state has to present the case to the jury, and then the jury will deliver justice. That's their job - to deliver justice. If I don't leave anything undone in that search for the truth, then I'm at peace."

I ask Mr. Muniz if he believes in the existence of evil. He says, "Evil, as I understand it, is not an entity. It is the absence of good. I don't see evil as a power that swoops and invades somebody."

Two of Mr. McNeal 's friends told police that he was the shooter, and Mr. Muniz believes them.

"There's nothing different about D.T., except who he decided to listen to," he says. "D.T. listened to the bad influences in his life and in his own mind. So he didn't care about anybody else. It was just a horrible, tragic accident that he collided with David on that day. But it could have been absolutely anybody else. So I don't think we can avoid that kind of evil."Satan doesn't reach up and kill somebody. It's a human being that kills a human being."

At D.T. McNeal's court hearing, Peter McNulty, one of David's brothers, said, "I forgive you."

Mr. Muniz was moved by this. He says, "That was what I would want my children to say. Because Christ was explicit about this. When a person forgives another person, it is the most divine thing we do. When Peter did that, he and his parents rocketed to the top of my esteem list. Because - there's peace."

In November of 2002, Mr. Muniz transferred to the sexual assault unit, so that he could spend evenings with his children. He tells me about helping his daughter with her homework.

"I blithely quote Scripture that we're created in the likeness and image of God," he says. "What I don't often think about is, 'What part of us is like Him?' Does He have arms and legs? No. It's an energy, it's intellect, it's reason. My little girl was studying for a science test and she threw out the Law of Conservation of Energy, which states, 'Energy cannot be created or destroyed.' I told her, 'Well, that's God. You can't create Him. You can't destroy Him. God is energy.'"

* * * * * *

The realization, again.

When we open ourselves up to love, there are no guarantees that we'll have the gift of that person forever. There's just the love we had, and the hope that we can sometime open ourselves up to love in that way again.

This is the hard truth.

- Journal entry, Dec. 23, 2000

* * * * * *

JONATHAN MCNULTY Jonathan McNulty, David's twin brother, remembers getting the urgent phone call from his family. "They called me at 5 in the morning. I said, 'What is it?' And they said, 'Just come over.' So I was thinking terrible thoughts but nothing close to that. I'll never forget - Dad standing in the bedroom.

Pete and Josh were there. Mom was sitting on the bed. They said, 'David's been shot.' And we sat and bawled. Just miserable."

Five months after David's death, Jonathan told me, "What is there to say as far as my feelings? I'm completely crushed. I already had questions about why we're all here. I don't see the need for so much suffering in the world. Thinking about it is so debilitating, that, when I'm by myself, it'll make me cry, sob, really. So in order to get out of that, I stop thinking. Thanksgiving was tough. We have a tradition that we go around and say what we're thankful for. And that was tough."

"I don't ask God, 'Why?' Because there's no answer to why my brother got shot, and that's what's so frustrating. Nothing will ever be the same. I feel a lot less joy. Joy seems almost like the wrong feeling. It's hard to get excited about daily life."

On the morning after David's funeral, I'd gone for a walk and came home to find David's parents standing in front of my home. They wanted to understand what had happened to their son David, and they needed reassurance that he had not suffered. They told me about the twins.

His father explained how David had childhood health problems that left him shy and nervous. Jonathan, on the other hand, excelled academically, athletically and socially.

Jonathan was a National Merit Scholar, was a starter on the basketball team at Richardson High School and went on to play college basketball at Trinity University in San Antonio. Jonathan McNulty, David's twin brother, remembers getting the urgent phone call from his family. "They called me at 5 in the morning. I said, 'What is it?' And they said, 'Just come over.' So I was thinking terrible thoughts but nothing close to that. I'll never forget - Dad standing in the bedroom.

Pete and Josh were there. Mom was sitting on the bed. They said, 'David's been shot.' And we sat and bawled. Just miserable."

Five months after David's death, Jonathan told me, "What is there to say as far as my feelings? I'm completely crushed. I already had questions about why we're all here. I don't see the need for so much suffering in the world. Thinking about it is so debilitating, that, when I'm by myself, it'll make me cry, sob, really. So in order to get out of that, I stop thinking. Thanksgiving was tough. We have a tradition that we go around and say what we're thankful for. And that was tough."

"I don't ask God, 'Why?' Because there's no answer to why my brother got shot, and that's what's so frustrating. Nothing will ever be the same. I feel a lot less joy. Joy seems almost like the wrong feeling. It's hard to get excited about daily life."

On the morning after David's funeral, I'd gone for a walk and came home to find David's parents standing in front of my home. They wanted to understand what had happened to their son David, and they needed reassurance that he had not suffered. They told me about the twins.

His father explained how David had childhood health problems that left him shy and nervous. Jonathan, on the other hand, excelled academically, athletically and socially.

Jonathan was a National Merit Scholar, was a starter on the basketball team at Richardson High School and went on to play college basketball at Trinity University in San Antonio.

* * * * * *

"No woman who is a woman says of a human body, 'It is nothing.' On this one point, and on this point almost alone, the knowledge of a woman, simply as woman, is superior to that of man; she knows the history of human flesh; she knows its cost; he does not."

- Olive Schreiner, 1911, "Women and Labour"

* * * * * *

FRANCES MCNEAL "D.T. told me that he did not shoot David. I believe what he told me," says his mother, Frances McNeal. "D.T. was getting ready to go to Prairie View A&M. He'd gotten accepted. He'd graduated in May of 2000 from DeSoto. I had to withdraw him from school. Anytime your child is involved in anything, it's hard on you. I couldn't see D.T. doing anything like this."

Mrs. McNeal, 60, graduated from Quitman High School in 1960 and received an associate's degree in business from Bishop College in 1966. She worked at Mobil Oil from 1966 to 1995 and from 1997 to 2002. She and D.T.'s father, George McNeal, divorced in 1991.

Mrs. McNeal is active in Concord Baptist Church. Family photographs decorate the wall of her living room. Shelves are packed with D.T.'s athletic trophies.

After D.T.'s arrest, Mrs. McNeal says, "I would come home and get on the couch and I wouldn't move. Some nights I just sat over in that corner and cried. My sister would call me and say, 'Let's go out to eat.' And I'd say, 'No, I don't want to.' Being a parent, I always wanted to fix it, fix it. But I couldn't fix it. There was nothing I could do."

I ask Mrs. McNeal how her son is doing. She says, "He's growing up. He was brought up in the church and went to church every Sunday. He was in the children's choir, he was in the youth usher board, and he was one of the steppers - the Joy Posse. He knew right from wrong. He was presented through the church. I think he's getting it together.

"As a little kid, D.T. was a joy to have," she says. "He was involved in football, T-ball, basketball. You could feel sad and he'd come out with a joke. I didn't have any problem with D.T. until he got to the 11th grade in high school. But he was always helping people - always being there for people." "D.T. told me that he did not shoot David. I believe what he told me," says his mother, Frances McNeal. "D.T. was getting ready to go to Prairie View A&M. He'd gotten accepted. He'd graduated in May of 2000 from DeSoto. I had to withdraw him from school. Anytime your child is involved in anything, it's hard on you. I couldn't see D.T. doing anything like this."

Mrs. McNeal, 60, graduated from Quitman High School in 1960 and received an associate's degree in business from Bishop College in 1966. She worked at Mobil Oil from 1966 to 1995 and from 1997 to 2002. She and D.T.'s father, George McNeal, divorced in 1991.

Mrs. McNeal is active in Concord Baptist Church. Family photographs decorate the wall of her living room. Shelves are packed with D.T.'s athletic trophies.

After D.T.'s arrest, Mrs. McNeal says, "I would come home and get on the couch and I wouldn't move. Some nights I just sat over in that corner and cried. My sister would call me and say, 'Let's go out to eat.' And I'd say, 'No, I don't want to.' Being a parent, I always wanted to fix it, fix it. But I couldn't fix it. There was nothing I could do."

I ask Mrs. McNeal how her son is doing. She says, "He's growing up. He was brought up in the church and went to church every Sunday. He was in the children's choir, he was in the youth usher board, and he was one of the steppers - the Joy Posse. He knew right from wrong. He was presented through the church. I think he's getting it together.

"As a little kid, D.T. was a joy to have," she says. "He was involved in football, T-ball, basketball. You could feel sad and he'd come out with a joke. I didn't have any problem with D.T. until he got to the 11th grade in high school. But he was always helping people - always being there for people."

* * * * * *

The world is not a thoroughly serene place. Obviously. Do we choose to live in the illusion of an oasis of serenity? Or do we buy into the concept of "one body"? Isn't that what Jesus asked? If we believe that we are one body, our body is terribly ill. We have to recognize that. This self-loathing ... is it original sin?

When one arm is ripping off the other, look in the mirror.

- Journal entry, April 29, 2003

* * * * * *

Linda Beth McNulty and I spoke frequently before her death. My research into murder and violence has left me, at times, in a dead end of futility. Then, in the quiet of my studio, I thought I heard Linda Beth whisper, "Speak, speak," and I persisted.

If there are such things as ghosts, and if David's energy lingered near my garden, I wanted him to find peace. And I wanted any remnants of brutality to be replaced by a sacred spot, filled with the presence of love.

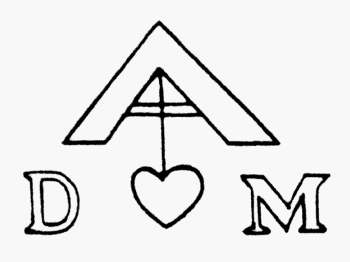

I planned a memorial service. An ancient symbol from the catacombs in Rome was a perfect design for a stone for the garden. It is Diis Manibus, which, according to a religious symbols book I have, means "to the spirit of the blessed" in Latin.

DM. Diis Manibus. David McNulty.

My husband made the stone memorial and left the heart shape empty in the middle.

On the night of the service, five weeks after David's death, the Dallas police shut down our street. Members of the McNulty family, their friends, neighborhood residents and police gathered on the spot where David McNulty was shot.

Four neighbors spoke. Linda Beth McNulty read a poem. The pastor asked for blessings for David, for Mark Hoesterey and Clay Odom, for the McNulty family, for all who loved David, for the Dallas police, for this place, for our neighborhood, for our city, for our nation.

The pastor poured water over the street. Everyone placed a white stone into the heart in the memorial.

One heart. One body.

One bullet. What a cruel, cruel path to communion. I planned a memorial service. An ancient symbol from the catacombs in Rome was a perfect design for a stone for the garden. It is Diis Manibus, which, according to a religious symbols book I have, means "to the spirit of the blessed" in Latin.

DM. Diis Manibus. David McNulty.

My husband made the stone memorial and left the heart shape empty in the middle.

On the night of the service, five weeks after David's death, the Dallas police shut down our street. Members of the McNulty family, their friends, neighborhood residents and police gathered on the spot where David McNulty was shot.

Four neighbors spoke. Linda Beth McNulty read a poem. The pastor asked for blessings for David, for Mark Hoesterey and Clay Odom, for the McNulty family, for all who loved David, for the Dallas police, for this place, for our neighborhood, for our city, for our nation.

The pastor poured water over the street. Everyone placed a white stone into the heart in the memorial.

One heart. One body.

One bullet. What a cruel, cruel path to communion.

Karen Blessen (kblessen@aol .com) is a Dallas free-lance writer and illustrator. |

ALL STORIES:: One By One By One:: One Bullet :: In Mom's Eyes :: Luck :: A Sea of Sound :: Diary of a Confetti Engineer :: What Did He See From the Mountaintop? :: Faces of a Plague :: What turns compassion into action? :: Today Marks the Beginning If you are interested in scheduling Karen Blessen for a speaking engagement or workshop, please call 214-827-3257 or e-mail kblessen@aol.com |

Contact Karen Blessen :: kblessen@sbcglobal.net :: Karen@29Pieces.org :: kblessen@TodayMarkstheBeginning.org :: 214-827-3257 :: Email Webmaster

KarenBlessen.com. Artist and writer. Cut paper collages, illustrations,

drawings, prints, stories, journal entries, public art, and photographs are

copyright Karen Blessen unless otherwise noted.